Key takeaways:

Theresa Wilbanks found steep challenges after becoming a caregiver for her father.

She struggled to overcome obstacles and manage complex emotions.

She’s now a caregiving advocate who offers strategies for avoiding burnout.

Theresa Wilbanks was living in France when she got the call: Her father had woken to smoke filling his Florida condo after some candles he lit burned into his dresser.

Her father — a World War II veteran and a retired teacher who liked to paint landscapes — was 93 years old. He closely guarded his independence. But Theresa decided she needed to be closer to him.

“He downplayed it,” she says. “But it was a big deal.”

Challenges of caregiving were more than she expected

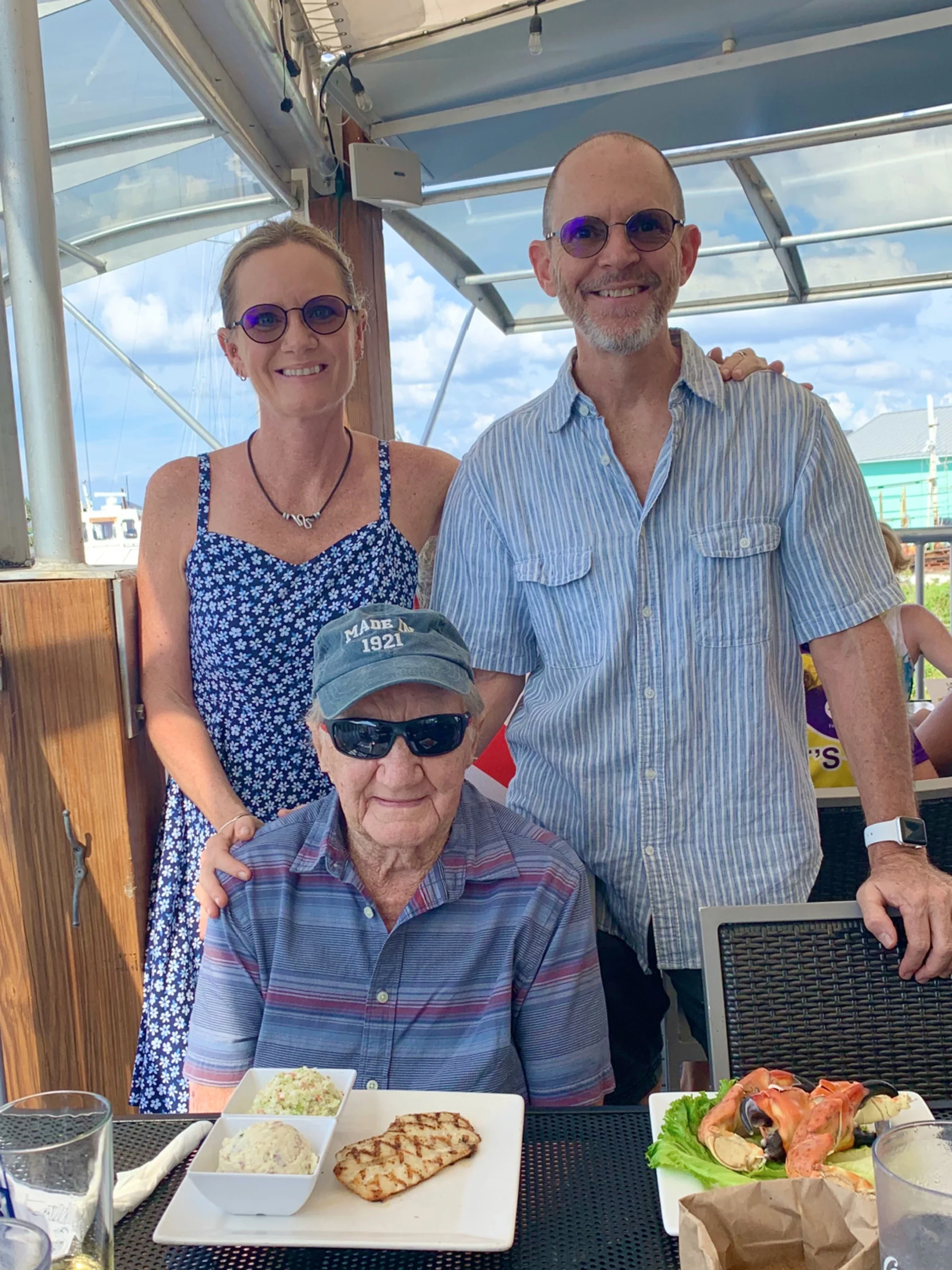

In 2014, Theresa, who’s now 58, and her husband, Joe, moved to Palm Harbor, Florida, to take care of her father, Richard Detwiler. In 2016, Richard had a stroke. He would later develop other ailments.

Theresa had seen her father taking care of his own parents as they aged. But he’d kept quiet about the struggles he faced as a caregiver. It wasn’t long before Theresa found those challenges steeper than she expected.

“It wasn’t until we got back that I saw the reality of it,” she says. “Everything I did all day long was either thinking about him or worrying about him or doing something for him.”

Theresa cared for her father for 6 years until he died at age 99 in 2020, after a heart attack and a bout with lung disease.

But that time brought some hard-won lessons about caregiving that Theresa put into a caregiving guidebook, aimed to help people in similar situations manage difficult emotions and prevent burnout.

These are some of her tips for sustainable caregiving.

Read more like this

Explore these related articles, suggested for readers like you.

1. Plan ahead before care needs arise

Theresa suggests having conversations with an older parent or loved one before care needs arise. Important topics include what they envision for their future, what they can afford, and how potential caregivers might fit in.

“If someone’s in their 50s, and their parents are in their 70s, it’s not too early to have this conversation,” she says.

That could include discussing issues around aging in place, which might head off future clashes over safety versus independence. Theresa says that became a flashpoint between her and her father. She says planning could also include speaking with a financial adviser and a lawyer to get matters such as power of attorney agreed upon and set up.

Theresa also suggests writing out potential concerns and plans to address them. For example, her father never moved into an assisted living facility, but Theresa researched potential obstacles ahead of time — such as what they might do if no bed was available in their nursing home of choice when her father needed it.

“I went and talked with someone there. I was able to understand the process if a hospitalization resulted in Dad not being able to come home and a bed wasn’t available,” she says. “It never came to that. But I had a plan written out just in case.”

2. Set boundaries, and accept help

Setting boundaries and personal limits — from the practical to the emotional — can be difficult because it can feel selfish, Theresa says. But it can save a caregiver time and energy while reducing stress.

One aspect of that is knowing when to get help. At first, she first helped her father two days a week. But that soon grew to daily help, which took an emotional toll and left her with little time to recharge.

“You might start by using grocery delivery, or you might have somebody sort and package pills or help with meals or bring in companion services that include light housekeeping,” she says. “It’s figuring out how you can lighten the caregiving load.”

Another boundary she set was helping her father in the shower or bathroom. She feared she lacked the strength to transfer him from his bed. And that would mean persuading her father to accept outside caregivers, something he initially resisted.

“I finally had to say, ‘I need help. I need help helping you,’” she says, noting that once her dad grew accustomed to nonfamily caregivers, he looked forward to time with them.

She learned that some emotional boundaries could ease her burden of worrying about his worries. Once, a hospice worker told her it was OK to sometimes deflect repeated discussions about his lung condition, conversations he had forgotten from the day before.

3. Become your own advocate

Theresa learned to become a strong advocate to overcome constant hurdles, including dealing with healthcare providers, she says.

Her father had health insurance. But she had to fight for a Veterans Administration medical benefit for hearing aids. His hearing loss was related to his work on a Navy ship that exposed him to loud engine noise, she says.

When that benefit was denied, in part because he had a pension, she had to fill out extensive paperwork to show his vast health expenses. They were still refused. She recalled being in tears once at a VA office, hoping her father didn’t see it.

“I didn’t want him to see me crying at that counter,” she says. But her advocacy paid off, and the hearing aids were eventually approved.

The next year, she had to go through it all again. But she persevered.

“You have to be your own advocate,” she says.

4. Take time for your own self-care

Theresa wanted her father to be safe, and he wanted his independence. “All of those things really create lots of conflict,” she says.

It also led to frustration. That included the time she walked in while her dad was on a 6-foot ladder trying to adhere one of his landscape paintings to the ceiling.

“Dad and I got along great, but now we were starting to have constant arguments,” she says. “Our relationship was suffering.

It was all part of a mix of difficult emotions around caregiving. She would get upset when providers or health systems fell short. And there was her own life. Would she and her husband be in Florida for years to come? Why weren’t other relatives helping more? Would she ever have time for the things she loved to do, such as traveling?

“I call it the cyclone — the guilt, anger, and resentment fueled by fear,” Theresa says. “That all started because I was resentful because I was helping so much and feeling guilty because I was feeling resentful.”

She learned that self-care was critical to maintain her energy and resilience during challenging moments.

She and her husband would take morning paddleboard rides and get others to cover her father’s care while they took short trips, such as hiking in Spain. She would express feelings in a journal and go running in nature.

“But by getting help in, we were able to go,” she says. “We were able to go out West and ski for a few weeks. That for me was personal and self-care.”

As caregiving responsibilities become more intense, even bite-size moments can help, she says. It might mean shorter sessions of yoga, less frequent tennis with friends, or listening to music on a walk instead of attending a concert.

And Theresa learned to let go of challenging feelings. She found gratitude in fellow caregivers, who became friends.

5. Reclaim control by letting go

One day, Theresa was reading to her dad from a stack of his journals, which included some of his own struggles with caregiving, including for his mother. That made Theresa realize that he had experienced some of the same feelings.

“He was worried about her,” Theresa says. “And he wrote what I was feeling — like pages and pages of frustration and anger and resentment and fear.”

After her father died, Theresa and her husband had to reconnect with their own lives, which were centered on her father for many years.

“I definitely felt this gaping hole. Upon waking up, the first thought I always had every morning was to go check on Dad,” she says. “It took us about a year and a half to really figure out what it was that we wanted to do and how we were going to do it.”

They were able to go on a long camping trip and figure it out. Joe worked remotely, and Theresa started to share caregiving tips online. Now they live in a recreational vehicle and travel the country, reconnecting with their love of travel.

In the end, Theresa says her caregiving journey was a gift. And it has allowed her to help others navigate that difficult task.

It was a rite of passage for the couple, Theresa says, and “a huge opportunity for growth for me.”

Why trust our experts?