Key takeaways:

New research from GoodRx shows that out-of-pocket costs vary widely across Medicare Part D plans, even for the same patient.

We estimate that the average Medicare patient enrolled in the average Part D plan overspends on their prescription drugs by $840 every year by not enrolling in the cheapest plan for their medication needs.

The worst Medicare Part D plan for the average Medicare patient can cost them nearly $3,200 more per year than the best plan.

Patients with costlier medication needs and chronic conditions like lung cancer, diabetes, and high blood pressure face even higher unrealized savings if they aren’t enrolled in the best plan for them.

Navigating healthcare in the U.S. can be complicated. Even under a national government health insurance program like Medicare, patients have to consider an overwhelming amount of information: what type of plan to enroll in, what’s covered, and how much needs to be paid out of pocket. Each of these considerations affects the cost and, ultimately, the amount of care that patients receive.

But even though these decisions are critically important, there are many barriers that prevent people from making the best decision for their healthcare needs.

One of these barriers is “inertia,” or the tendency to do nothing. It has been well documented when choosing health insurance plans, and it often results in patients overpaying for their health coverage. Many people wind up defaulting to a less-than-optimal plan, whether they get their insurance from their job, the commercial marketplace, or even Medicare.

To understand the extent to which these barriers could be hurting patients, GoodRx Research dug into thousands of Medicare Part D plans to estimate how much money patients could be leaving on the table. Part D provides prescription drug coverage for Medicare enrollees.

How much unrealized savings are Medicare patients losing out on?

First, we estimated how much out-of-pocket costs vary across Medicare Part D plans, even for the same patient. Then, we calculated the “unrealized savings” each Medicare patient faces on each plan, capturing the difference in annual out-of-pocket costs compared to their cheapest plan. These unrealized savings demonstrate just how different a patient’s cost burden can be depending on the plan they enroll in.

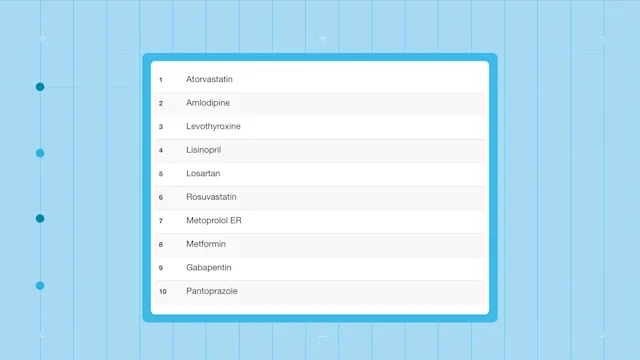

While the best plan for the average Medicare patient costs $544 per year (including prescription drug premiums), the average part D plan costs $1,384 per year for the same medications. So we estimate that the average Medicare patient enrolled in the average Part D plan overspends on their prescription drugs by $840 every year by not enrolling in the cheapest plan for their medication needs.

The worst Medicare Part D plan for the average Medicare patient can cost them nearly $3,200 more per year than the best plan, amounting to over $3,700 in total annual out-of-pocket costs for medications.

Our analysis shows that out-of-pocket costs vary widely across Medicare Part D plans. If patients are not choosing the best plan available to them, they could end up substantially overpaying for their medications.

Picking the right Medicare plan is especially important for patients with chronic conditions and high medication costs

Chronic conditions like lung cancer, cervical cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and diabetes not only result in greater medication needs for patients but also wider variations in out-of-pocket costs across Medicare prescription drug plans.

Read more like this

Explore these related articles, suggested for readers like you.

As the chart below shows, patients diagnosed with these conditions face higher unrealized savings than the average Medicare enrollee. These patients could save hundreds if not thousands of dollars if they enrolled in the cheapest plan for their medication needs.

These conditions are often treated using brand drugs with no generic version or a cocktail of multiple costly drugs. For example, first-line diabetes treatments like Trulicity and Januvia are brand drugs that aren’t always covered by insurance. If a patient enrolls in a plan that doesn’t cover these drugs, they could end up paying completely out of pocket every month for these medications.

Summing it all up

In the end, patients are the ones hurt by inefficiencies in the healthcare system. By not enrolling in their optimal insurance plan, many people could face unnecessarily high healthcare prices that they may not be able to afford.

As a result, some people may struggle to pay for other essential expenses like food and shelter, while others may skip taking their prescribed medications altogether. This could lead to avoidable hospitalizations, disease progression, and even premature death, which all increase costs for both other patients and the healthcare system.

Higher medical costs may also increase patient distrust in providers, feeding into a negative cycle of patients not getting the care they need and experiencing worse, more expensive health outcomes.

On the flip side, if patients were always able to enroll in their best insurance plan, they could recapture hundreds if not thousands of dollars in unrealized savings — money that they could spend on their prescribed medications or otherwise taking care of themselves. Closing the unrealized savings gap could have a substantial impact on not only medication adherence, but also on health outcomes and healthcare spending.

Read the full analysis in our white paper.

Co-contributors: Lauren Chase, Trinidad Cisneros, PhD, Jeroen van Meijgaard, PhD, Tori Marsh, MPH, Sasha Guttentag, PhD

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2019). Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Campbell, P. J., et al. (2021). Hypertension, cholesterol and diabetes medication adherence, health care utilization and expenditure in a Medicare Supplemental sample. Medicine.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022). Medicare Advantage/Part D contract and enrollment data.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022). Prescription drug plan formulary, pharmacy network, and pricing information files for download.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022). The Inflation Reduction Act lowers health care costs for millions of Americans.

Chandra, A., et al. (2021). The health costs of cost-sharing. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cubanski, J., et al. (2021). Medicare Part D: A first look at Medicare prescription drug plans in 2022. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Cunningham, P. J. (2009). High medical cost burdens, patient trust, and perceived quality of care. Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Drake, C., et al. (2021). Sources of inertia in health plan choice in the individual health insurance market. SSRN.

Fuglesten Biniek, J., et al. (2022). Medicare beneficiaries rarely change their coverage during open enrollment. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Handel, B. R., et al. (2015). Health insurance for" humans": information frictions, plan choice, and consumer welfare. American Economic Review.

Hill, S. C., et al. (2011). Implications of the accuracy of MEPS prescription drug data for health services research. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing.

IPUMS. (2022). Use of samplings weights with IPUMS MEPS.

Jha, A. K., et al. (2012). Greater adherence to diabetes drugs is linked to less hospital use and could save nearly $5 billion annually. Health Affairs.

Marsh, T., et al. (2021). The Big Pinch: New findings on changing insurance coverage of prescription drugs. GoodRx Health.

Medicare. (2022). Costs for Medicare drug coverage.

Medicare. (2022). Explore your Medicare coverage options.

Medicare. (2022). Joining a health or drug plan.

Ochieng, N., et al. (2022). A relatively small share of Medicare beneficiaries compared plans during a recent open enrollment period. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Riaz, A., et al. (2021). How agents influence Medicare beneficiaries’ plan choices. The Commonwealth Fund.

Roebuck, M. C., et al. (2011). Medication adherence leads to lower health care use and costs despite increased drug spending. Health Affairs.

Ruoff, A., et al. (2022). J&J, Amgen, Regeneron drugs likely to face Medicare negotiation. Bloomberg Law.

Sokol, M. C., et al. (2005). Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Medical Care.

Stuart, B., et al. (2011). Does medication adherence lower Medicare spending among beneficiaries with diabetes? Health Services Research.

Zinman, B., et al. (2015). Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine.

Why trust our experts?