Key takeaways:

My grandfather passed away this spring by medically assisted death.

It can be hard to find the right words to say or know what to do when someone you love chooses to die.

Ultimately, all you can do is support the person in their decision and make sure they know they're loved.

The last email from my grandad still sits at the top of my inbox, received March 29 at 10:58AM. Four hours and two minutes before his appointment with death.

The subject line reads “Re: ‘I love you!’” in response to my email earlier that morning. Timestamped 7:31AM. I’d started writing it as soon as I woke up, typing and then erasing sentences. How do you cram a lifetime into one message?

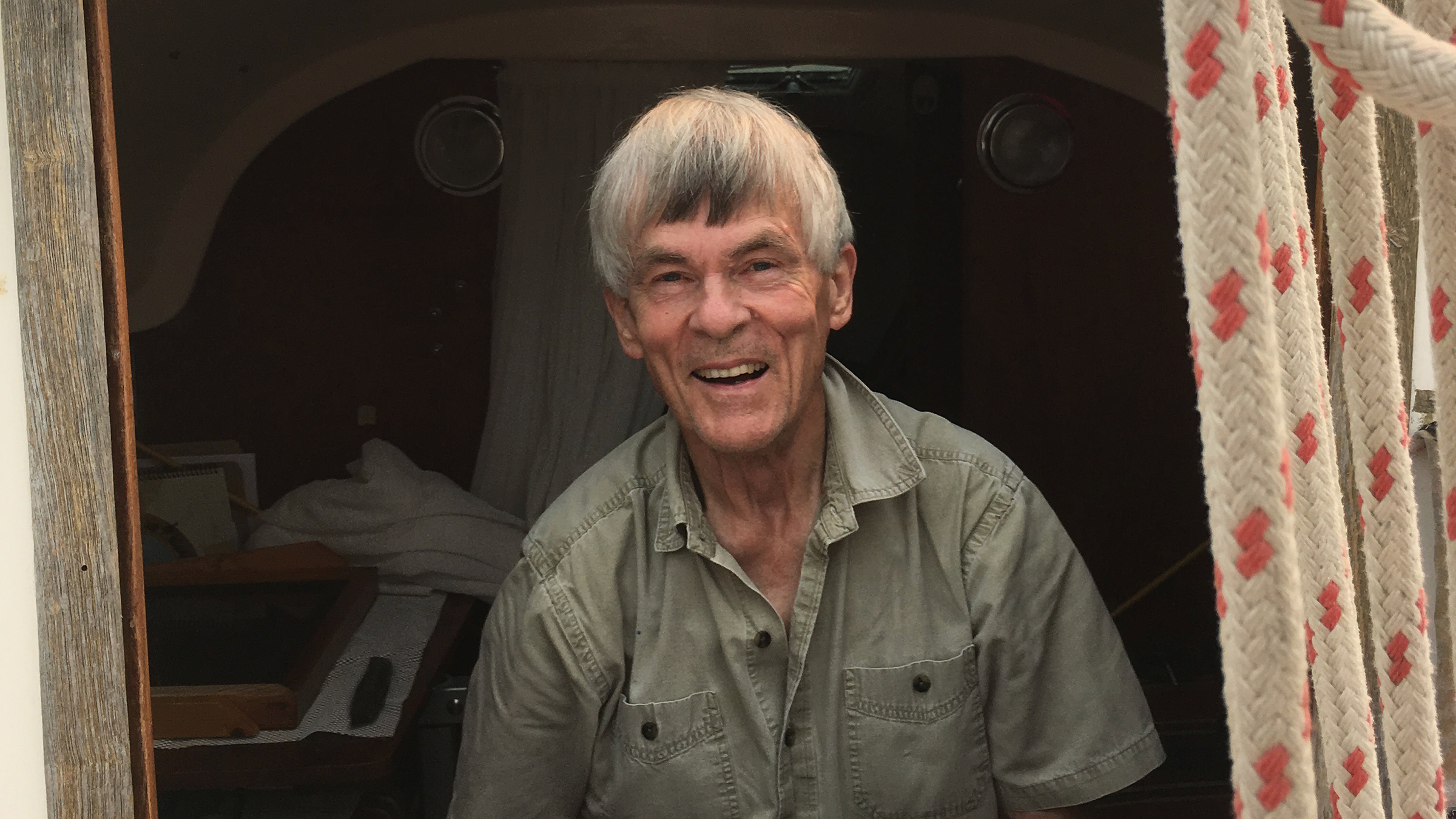

In the end, I settled on a few paragraphs about happier times and attached some photographs — a selfie taken on his sailboat during a chilly crossing of the Strait of Georgia, a snap of us sitting on the beach together right after I’d finished university, and a picture of us rowing a small boat out into a calm harbor. Then, I hit send, hoping he still had access to his computer to see it in time.

We’d already said our goodbyes over the phone a couple days earlier, when I first found out that he had decided on a medically assisted death and set the date.

It felt strange to say nothing, to not acknowledge the moment on the day. And he’d always preferred written messages over phone calls anyway.

But is 5 hours and 29 minutes enough time to give someone to check their email on the day they die? There are no protocols, no norms to follow when someone you love has chosen physician-assisted death.

Medically assisted death: A recap

Medically assisted death, also sometimes known as physician-assisted suicide, is when a healthcare practitioner provides or administers a medication that causes death to someone who has requested it.

In most parts of the world, helping someone die is a crime.

But in some countries, it’s legal under specific circumstances. My grandad lived in British Columbia, Canada, where medical assistance in dying (MAiD) is allowed for people over the age of 18, who have given informed consent and have a “grievous and irremediable medical condition,” among other requirements.

In the U.S., the legality and requirements differ state to state. Assisted death is currently authorized in 10 states and the District of Columbia, but not permitted in others.

Read more like this

Explore these related articles, suggested for readers like you.

It’s a widely controversial topic, with divided political and ethical opinions. Much of the debate centers on whether it’s considered suicide, whether someone needs to have a terminal disease or just an incurable disease to be eligible, and how mental illness or other disabilities fit into the equation.

I can’t speak for everyone’s journey. But from what I experienced, it looks an awful lot like suicide. You can understand all the logical reasons why someone you love chooses to end their life but still want to yell out: “No, stop! Come back! There’s still hope!”

Of course, you can’t say that, though. All you can do is support them the best you can and make sure they know they’re loved. Like with an email filled with memories and loving words and no judgments.

The right words to say

That email still sits in my inbox, months later. It’s an old Hotmail account, one I made in high school before I learned people take you more seriously with Gmail.

I kept it active to continue email chains with my grandparents. By 2022, only my grandad was still alive to correspond with through the decade-old account. Now, there are no new messages coming in to bump that last email down the line. So there it lingers, at the top.

I’ve reread it countless times now, wondering if I should have said something different. If there was anything I could have said that would have made a difference. Maybe if he had felt like there was hope, something to alleviate his pain and loneliness. A reason to keep living. A lifeline crafted with the perfect words. I don’t know if that’s something you can give someone, though. Or if the right words even exist.

I wasn’t surprised when I heard about my grandad’s decision. He had never really discussed dying with me in all the time we spent together — other than the occasional macabre joke. But taking matters into his own hands did seem like something he would consider.

He was an extremely independent man, and I know he mourned his diminishing self-sufficiency as prostate cancer stole pieces of his health. He’d always been ahead of the curve: a steadfast vegetarian before it was cool, an early Apple computer adopter, a man who lived on a small hippy-ish island off the West Coast for more than two decades. A former university professor with a fiery zest for debating politics, history, science, and ethical dilemmas, like assisted death.

Under different circumstances, it’s a topic we would have dug into over a dinner date.

A different outcome in a different time?

The last time I saw my grandad was a few months before his death. He was as he’d always been: so very much alive and himself, despite his illness. I had moved from Vancouver to California by this point. But I spent the summer driving back and forth on three occasions for multi-week visits.

I have a photograph of him from one of those last visits, standing on a daybed and looking down at me with a schoolboy-like grin. He’d clamored up, walker and all, to restick a poster that had come loose from the wall in his home office. I was equally impressed and horrified, gently chiding him for not having called me over to fix it for him.

By spring, those last wisps of independence must have looked like they were dissolving. My granddad sold his home and moved off the island into a retirement home.

He kept his car, but it remained undriven. He brought a wheat grinder and several dozen kilograms of grain with him to make his legendary bread, but they gathered dust in a corner of his new apartment. He ordered a mobility scooter for grocery shop runs, but waited months for it to be fixed. He lamented that fact to me over the phone, noting that previously he would have gone to the store, bought the necessary parts, and got it running himself in an afternoon.

And perhaps most detrimental of all, COVID-19 mandates restricted visitors to the retirement home and made international travel to return to Canada challenging. I know he was lonely and struggling. He told me as much when I’d call. Yet, I could never find the right words to reassure him.

Words couldn’t change the outcome, but I can’t help but believe that actions might have. Death is inevitable for all of us. But maybe different actions in a different time would have helped my grandad keep living till the end rather than merely existing for those last few months.

I’ve heard people debate whether they’d want to know the time, place, or manner of their own death. For those who are left behind, the knowledge leads to more questions than answers.

Why trust our experts?