Key takeaways:

Rebecca Denison has lived with HIV for almost 40 years.

Her first years with the diagnosis were scary. But she became a mother of HIV-negative children and an activist who helped other HIV-positive women.

She’s proof that not only does life go on after an HIV-positive test result, but life can also be rewarding and happy.

Rebecca Denison learned she was HIV-positive by chance.

She was happily married, working at a law firm, and preparing for law school. When a friend confided that her sister was dying of AIDS, Rebecca offered her support. Her friend wanted to be tested for HIV (the human immunodeficiency virus, which causes AIDS), but had told Rebecca she was so scared she was afraid she’d back out.

“I told her, ‘You’ll be fine. I’ll go with you,’” Rebecca recalls.

Rebecca got tested herself.

HIV/AIDS misconceptions

Rebecca’s friend tested negative. But when the health center worker gave Rebecca her test results, everything stopped. Her test was positive.

“All the cliches proved to be true,” Rebecca says. “The room spun … I froze. It was like being hit by a truck you didn’t even see coming.”

Rebecca held her breath until she realized she’d stopped breathing. Then, she remembers thinking: “Oh, my god. If I have it, my husband probably has it.”

Her next thought was: “I’m never going to be able to have a baby,” Rebecca recalls.

This was 1990. At the time, Rebecca thought that someone who had AIDS would be sick, and she wasn’t. “I didn't really wrap my brain around the idea that you could be a carrier of something for like 10 years before getting sick,” she says.

Her other misconception, widely held at the time, was that non-IV-drug using women really didn’t get HIV.

- Emtricitabine/TenofovirGeneric Truvada

- VireadTenofovir

- Biktarvy

Her husband, Dan Johnston, a teacher, was studying Spanish in Guatemala at the time but flew home immediately.

“He never treated me like a germ, not before, or after, he found out he was HIV-free,” Rebecca says.

“I survived thanks to the amazing support of family and friends.”

Creating a support network for HIV-positive women

Rebecca’s diagnosis changed the course of her life. Instead of going to law school, she kept her job so that she could keep her health insurance. Her HIV diagnosis would have made her “uninsurable” in 1990, she says.

She had trouble finding information about what to expect or do. Her searches for a support group or legal advice were unsuccessful.

“I kept getting turned away, either because I was a woman or I wasn’t sick enough,” she says.

She didn’t want other women to go through what she went through. She says she dreamed of a place where people would say to her: “We’re glad you called. We’re here for you. It doesn’t matter how you got it. It matters that you get support. We welcome every aspect of your identity.”

So, in 1991, she founded an HIV/AIDS education and advocacy group called WORLD (Women Organized to Respond to Life-threatening Diseases) for HIV-positive women that is still operating today. It started as a way to connect women in the San Francisco Bay area but grew into something more.

“I didn’t know how to start or lead a non-profit,” Rebecca says. “But maybe that was a good thing, because it led to an organization with a lot of shared decision-making and tons of volunteers from all walks of life.”

The joy of motherhood

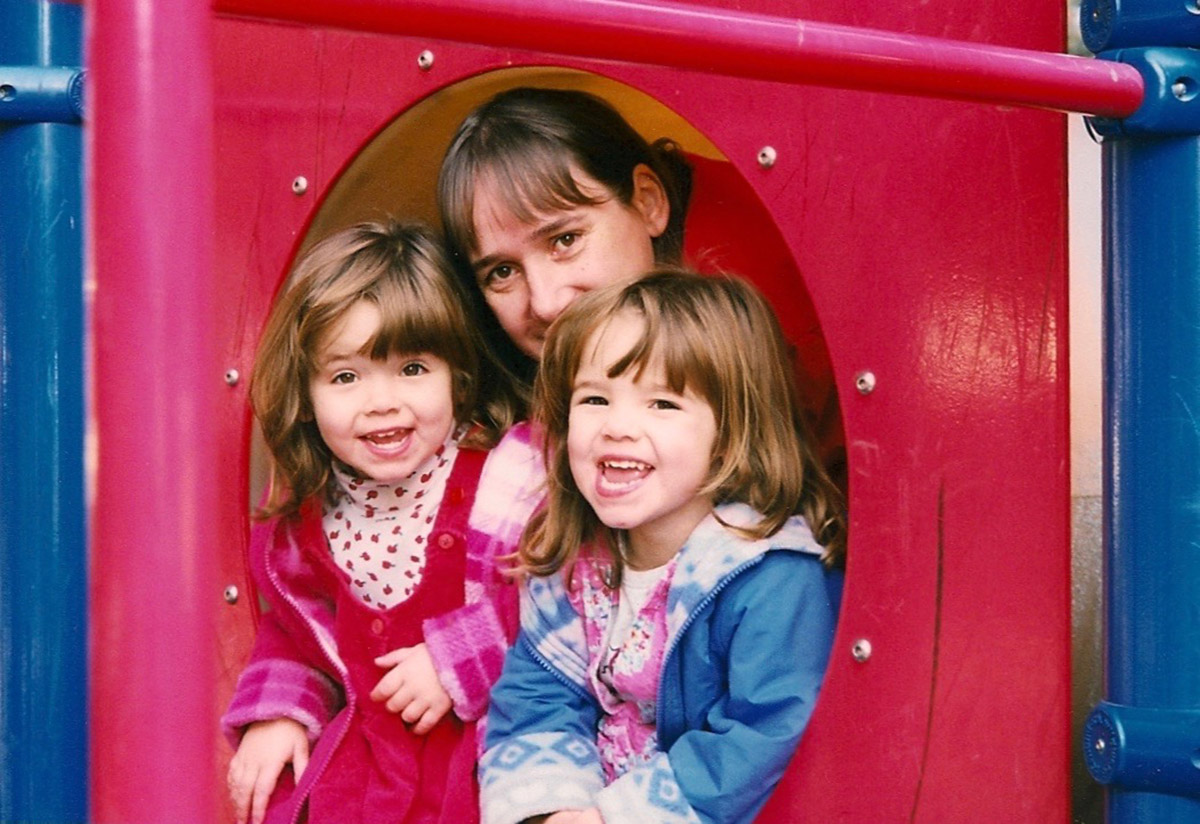

Rebecca says she never believed people needed to have kids to live a full life. Yet, her diagnosis made her “grieve not being able to be a mom more than thinking I would die young,” she says.

She assumed she wouldn’t live long enough to raise kids or that pregnancy would put her baby’s life in danger. But by 1994, a landmark study called ACTG 076 produced results showing that pregnant women treated with antivirals had a greatly reduced risk of having an HIV-positive baby. That gave Rebecca hope. She and her husband began to explore how they could safely have a baby.

In 1996, Rebecca gave birth to healthy HIV-negative twin girls.

Around the same time the girls were born, a new class of medication called protease inhibitors came out.

“At that moment, I thought: ‘Some of us are going to make it. I could be one of the people who survives this,’” Rebecca says. For her, it was a revolutionary idea. Until then, she says, people assumed that everyone with HIV would die from it eventually.

Since the advent of protease inhibitors, a multitude of advances have been made including the establishment of clinical proof for the idea that “U=U.”

U=U means that people with HIV who take anti-HIV treatment medications as prescribed and achieve and maintain undetectable viral loads (the amount of HIV in blood), cannot sexually transmit the virus to other people: undetectable = untransmittable.

Rebecca emphasizes that U=U represents a “really important improvement in quality of life for people living with HIV.”

Life today: Strategies and learnings

Today, Rebecca is a 60-year-old HIV writer and educator in Berkeley, California. After living with HIV for almost 40 years, she’s proof that life goes on. She’s now a grandmother. And she says she’s learned to take better care of herself and her loved ones.

“I used to assume I would die soon,” she says. “Now, I assume I’ve got a while. But in either case, I don’t have time to waste doing work that’s not meaningful or hanging out with toxic people.”

Her diagnosis taught her that “things can change in the blink of an eye,” she says. From the moment she was diagnosed, she’s told people that she loves them and what she appreciates about them. Or she thanks them, without waiting for a special moment.

She also focuses on self-care.

“When you’re healthy, taking care of yourself can seem like a low priority,” she says. “But when you’re not healthy, it’s the only thing that matters.”

Why trust our experts?