Key takeaways:

Campylobacter is a bacteria that’s a common cause of food poisoning worldwide. Infections are more common in summer months, likely as a result of meat not being thoroughly cooked or stored at cookouts.

Most people with a Campylobacter infection will have diarrhea for about a week. Most people are able to recover at home, by resting and rehydrating with electrolyte-rich fluids.

A small number of people may get a more severe infection that results in bloody diarrhea and intense abdominal pain. These cases require medical attention.

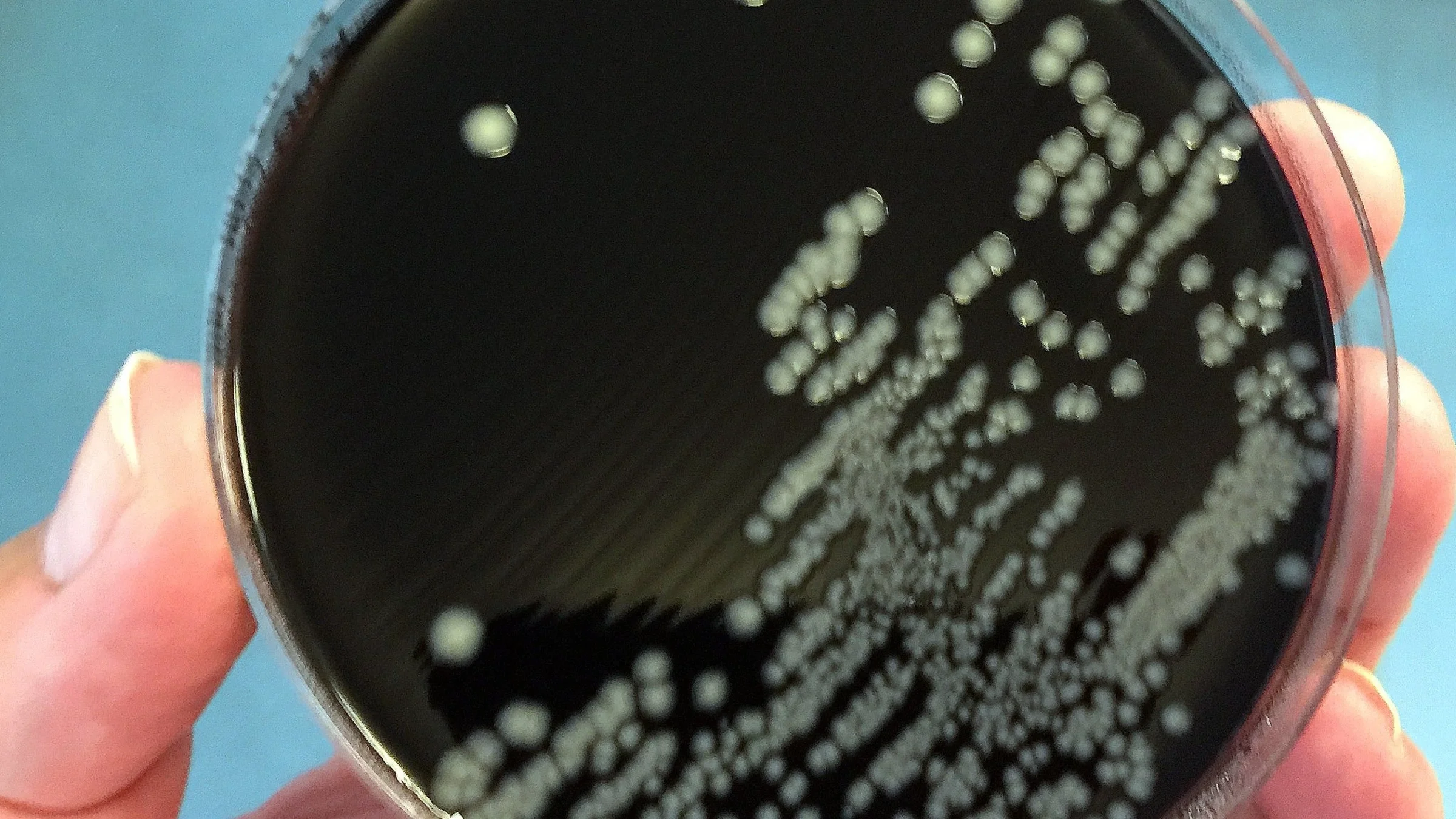

FeaturedImage

Campylobacter is a bacteria that causes food poisoning in both developed and developing countries. In the U.S. alone, there are an estimated 1.5 million cases of Campylobacter infection a year.

There are many strains of bacteria in the Campylobacter family, but the most common one is C. jejuni. These strains are particularly virulent, meaning that it only takes a small amount of bacteria to cause an infection.

If you do get a Campylobacter infection, there are steps you can take to recover at home, as long as you don’t have a severe case that requires medical attention.

How do you get a Campylobacter infection?

Over 90% of cases of Campylobacter infection happen during the summer months. (This is thought to be a result of meat not being thoroughly cooked — or properly stored — at cookouts.) But you can get it any time of year.

There are several ways that you can get sick from Campylobacter, including:

Contaminated food and water: This is the most common way Campylobacter spreads. People can get sick when they eat meat or other food that is not fully cooked or hasn’t been stored properly. And, in areas where there is poor access to sanitation, it may be an issue of the water not being clean enough to drink.

Animal contact: People can also get sick after touching certain animals. Poultry are often blamed for outbreaks of Campylobacter, but the bacteria is also commonly found in cattle and pigs. Outbreaks can also happen in meat processing plants. If the slaughtered animals are infected with Campylobacter, all of the meat being processed can be contaminated.

Person-to-person contact: Similar to other bacteria that cause food poisoning, Campylobacter can spread through fecal-oral transmission. This means that someone who has a Campylobacter infection and does not wash their hands well can spread the bacteria to others. This can be from direct contact, through shared surfaces like door handles, or through shared food and drink.

Common symptoms of a Campylobacter infection

In general, people feel sick within 24 to 72 hours of contact with the bacteria. Common symptoms include:

Fever: People usually experience high fever a day or two before the diarrhea starts.

Chills or rigors: Along with the high fever, people can experience shaking chills.

Diarrhea: Stool is often described as mucous-like, but it can also be bloody.

Nausea and vomiting: Vomiting can occur along with diarrhea.

Abdominal pain: Intestinal cramping can also accompany the diarrhea.

Most symptoms resolve within three days. But the diarrhea can last up to a week, during which it can happen frequently (as many as 10 times a day).

- FlagylMetronidazole

- SulfatrimSulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim

- BactrimSulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim

How is a Campylobacter infection diagnosed?

Similar to other types of food poisoning, many people with a Campylobacter infection do not see a healthcare provider for evaluation. Often, the illness passes on its own and there’s a quick recovery.

If a person does seek medical attention, like in severe cases, a provider may order a stool sample to confirm the diagnosis. However, identifying the specific bacteria behind a case of food poisoning isn’t always important. This is because the treatment is the same regardless of the bacteria causing the problem.

Treatment for a Campylobacter infection

With a Campylobacter infection, most people have a mild illness and recover on their own at home. For healthy people without other medical conditions, the treatment includes:

Hydration: Frequent episodes of diarrhea and, potentially, vomiting can lead to dehydration. So it is important to keep yourself hydrated. Take small, frequent sips of clear fluids, even if you are vomiting. (Larger sips can lead to more vomiting.) Avoid liquids with a lot of sugar, because they can often make diarrhea worse.

Electrolyte repletion: Along with fluid, your body loses electrolytes (salts) when you’re having frequent bowel movements. Broth, Pedialyte, and sport drinks with electrolytes will help you stay hydrated and recover quicker.

Avoiding anti-diarrhea drugs: Medications like Imodium (loperamide) and Lomotil (diphenoxylate/atropine) can actually interfere with your body’s ability to clear the infection. This can slow down your recovery.

Some people get a more severe infection and need to seek medical attention to get treated. In these cases, treatment can include:

IV fluids: Sometimes, with fluid loss from both vomiting and diarrhea, it can be hard to hydrate enough to keep up. And some people, especially older adults, can become dehydrated more easily. Fluids with electrolytes can be given intravenously to help rehydrate.

Antiemetics: It can be hard to drink fluids if you are extremely nauseated or vomiting frequently. In these instances, you may need medication to help with the nausea.

Antibiotics: Most people do not need antibiotics. But in severe cases, especially with people who have weaker immune systems, antibiotics can help.

People with severe infections should seek medical attention sooner rather than later. This will make the recovery process faster.

When to seek medical attention

Although most people get better at home, some need more advanced treatment for a Campylobacter infection. This is especially true for people who are immunocompromised.

Whether immunocompromised or not, anyone with these symptoms should seek medical attention:

Bloody stools: A small amount of blood in the stool can be a normal part of a mild infection. But you should see a provider if you see large amounts of blood or have several bloody stools per day.

Dizziness: This can involve feeling lightheaded, like you’re going to pass out, or like you’ll fall down if you sit up or stand. This can be a sign of losing too much fluid and/or blood.

Abdominal pain: The abdominal pain caused by a Campylobacter infection can continue even after the diarrhea has resolved. Sometimes, the pain is so severe that the infection is confused with conditions like appendicitis. Since it can feel like other things, it’s important to make sure the cause of the pain is the Campylobacter infection.

Weakness and/or numbness: In rare cases, Campylobacter infections can lead to a complication called Guillain-Barré syndrome. This usually starts with feeling weak or numb in the legs. Sometimes, people have trouble walking. Others may feel weakness or numbness in their face.

Unable to stay awake: If someone seems really drowsy or is having a hard time staying awake, this is a sign of a severe infection that needs treatment.

If you or someone you know has any of these above symptoms, seek medical attention immediately.

Food poisoning prevention

A Campylobacter infection can happen to anyone. But there are some instances in which a few precautions can help keep you from getting sick.

These habits are good preventative measures:

Practice good hand hygiene. Wash your hands before eating or touching your face, especially if you are sick.

Keep raw meats separate. By keeping meats separate from other foods, you can prevent cross-contamination.

Cook food thoroughly. Avoid eating partially cooked meats.

Drink pasteurized milk and clean water. This is especially important in areas of the world in which water is not always sanitized. Drink bottled water in these instances.

The bottom line

For most people, food poisoning is a weeklong nuisance. If you have a Campylobacter infection, you can generally get better at home, by resting and drinking fluids. But, if you are having symptoms of a severe infection or have a medical condition that puts you at a higher risk for a severe infection, go see a healthcare provider. You may need testing or medication to make a full recovery.

Why trust our experts?

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Campylobacter (campylobacteriosis).

Epps, S. V. R., et al. (2013). Foodborne Campylobacter: Infections, metabolism, pathogenesis and reservoirs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Fischer, G., et al. (2022). Campylobacter. StatPearls.

Nolan, C. M., et al. (1983). Campylobacter jejuni enteritis: Efficacy of antimicrobial and antimotility drugs. American Journal of Gastroenterology.