Key takeaways:

It is possible to grieve for someone who is still alive, especially if they have a progressive condition.

When someone has a condition like Alzheimer’s dementia, their family often feels like they are slowly losing the loved one they once knew.

Grief can be a lengthy and ongoing process, especially when a loved one has a condition that progresses from early to late stage.

We often think of grief as a process that occurs after the death of a loved one.

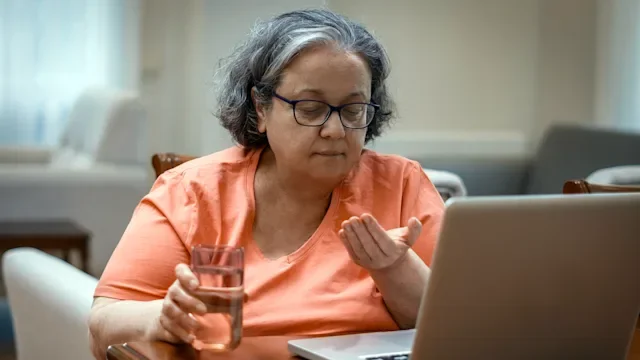

But for people who care for someone who has a diagnosis like Alzheimer’s — a type of dementia — grief is a process that begins while their loved one is still alive. Dementia disorders cause a progressive decline in memory, thought processing, and daily functioning. And Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia.

Below, three people share their experience with grieving the loss of a loved one who was or is living with Alzheimer’s.

Search and compare options

A grief unlike any other

When Karen DiBrango’s mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2016, her parents tried to conceal the diagnosis from the rest of the family for a while. But, by 2018, the family began noticing obvious signs of the disease progressing. At the time, Karen’s mom was also starting treatment for lymphoma.

“She put a bread basket in the oven to keep rolls warm, but the basket was made of straw,” says Karen, who is 51 and lives in Florida. “Or she would leave appliances on. Or we would find random things in the wrong places. She often forgot conversations we had or plans we had made.”

Karen says that, during that time, her father began to worry about leaving her mother unattended.

“My younger sister had noticed mom was hallucinating at times — mostly when she was very tired, had a glass of wine, or was taking her chemo medications,” she says.

The diagnosis was difficult for Karen, her family, and her mother. “My mother grew very frustrated. She didn’t like to go out or socialize as much anymore,” Karen says.

Watching her mother decline and lose touch with who she was — and who they were — was hard, she adds. “It was the saddest thing I have ever lived through, aside from watching my father grieve the loss of his wife — the love of his life,” she says. “It was just heartbreaking.”

- NamendaMemantine

- AriceptDonepezil

- Memantine ERGeneric Namenda XR

Despite the heavy weight of grief, Karen says, her family found small ways to find joy and meaning in the time they had left together.

“We did everything we could to celebrate the little things, and to meet her where she was in the moment,” Karen says. “If Mom thought she had a gentleman suitor, then we dressed her up, did her hair and makeup, and brought my father to her room to enjoy their favorite dessert. She would fix his collar and run her fingers through his hair. It was beautiful yet heartbreaking all at once.”

Moments like those brought the family glimpses of the woman they knew, so full of life and love. But they also reminded them just how much had changed. Karen says that toward the end of her mother’s life, the grief became even more difficult for her father because, at that point, her mother was no longer able to connect with him.

“Alzheimer’s disease truly is the long goodbye," Karen says.

Handling the range of emotions that came with slowly losing someone so important was challenging. “I have felt every emotion tied to this grief, including anger. It’s tough to deal with.” Karen says. “I just cannot believe that is how she left this world.”

Despite her mom’s passing in January 2020, Karen says her memories will live on.

“What I remember most about my mother was her positivity and her determination,” she says. “This combination made her a force to be reckoned with. She loved life and never met a challenge she couldn’t overcome, outwit, or maneuver around. She taught her kids to always appreciate our blessings, to be a blessing to others, and to never let life get us down.”

Disappearing before your eyes

Karen Edwards is 56, close to the age her husband was when he was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s.

At a time when she thought she’d be entering her retirement years with him, Karen became a caregiver for her husband, Howard, who’s now 63 and in hospice memory care.

The Phoenix couple first saw signs of Howard’s health issues in 2015, when he began showing mild symptoms of Alzheimer’s. At the time, he was struggling with work-related tasks and having issues with memory recall. But a neurologist told the couple the symptoms were just stress-related.

By 2017, they relocated from North Carolina to Arizona. The goal was to reduce stress. But in the new environment, Howard’s symptoms began to worsen. A visit to a second neurologist, followed by a neuropsychiatric consultation, gave the couple a heartbreaking answer. Howard was officially diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Karen says that one thing that having a loved one with Alzheimer’s has taught her is that it is very possible to grieve someone while they are still alive.

“I didn’t know what to feel,” Karen says. “It was the one disease I never wanted either of us to deal with. I had met people whose spouses died of it, and it was so sad.”

Karen had hoped that her husband’s illness would progress slowly and afford them more time together, but time was not on their side.

“Early on, his personality didn’t change. He just had frustration at not being able to remember things and felt embarrassed at work when they would get angry with him for not doing his job correctly,” she says. “It initially appeared to everyone that he was just not trying or being lazy. As he progressed into the moderate stage, he began to be more and more fearful and had extreme separation anxiety.”

Over time, Karen’s role shifted from being a partner to her husband to being more like a parent.

“I had to constantly make sure he was safe, not wandering off, fixing all of his meals, helping him get dressed, finding someone to stay with him when I was at work or traveling for work,” she says. “It was mentally and emotionally exhausting. There are no words for the toll that 24-hour-a-day care, combined with exhaustion and fear, has on a person. I have no idea how I survived that.”

By April 2022, Howard’s condition had worsened, and he was admitted to a full-time care facility. While Karen understood that this was a necessary arrangement, she still felt overwhelming grief.

“You can’t help but grieve as you watch your partner decline and become more helpless and more confused,” she says. “They are literally dying right in front of your eyes, little by little each day. It’s like watching a traffic accident on repeat — only, each day, the accident gets a little bit more traumatic.”

“The person I knew is barely there now. The Howard I married died a long time ago,” she adds. “You can absolutely grieve someone while they are still alive, especially as the person you love changes physically and mentally — and as you watch them deteriorate slowly, day after day.”

Karen continues to hold on to the pieces of the man she remembers so fondly.

“Tiny glimmers of himself show up now and again with a facial expression he used to make or when he laughs or tries to put his arm around me,” she says. “That tells me he’s still in there somewhere.”

Seeing the roles reversed

With Alzheimer’s, like with other kinds of dementia and progressive diseases, it’s common for adult children to switch roles and care for their declining parents.

Kim Van Hassel, who lives in Ringwood, New Jersey, cared for both of her parents through progressive diagnoses. Kim’s mother was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, and her father was diagnosed with vascular dementia. While they both passed away about 18 years ago, she still holds on to the fond memories of the years she had with them.

Recalling the early days of her father’s diagnosis, Kim says the main sign that something was wrong was that he was becoming more and more forgetful. He would become disoriented and forget where he was from time to time.

As both of her parents’ health continued to decline, Kim became their full-time, live-in caregiver.

“My father had some ability to understand what was going on throughout his illness,” she says. “But he was changing. He couldn’t drive anymore. He wasn’t allowed to be alone anymore. I felt really bad he was losing his independence. So I had to stay there.”

Kim says that, when she was growing up, her father was always a wonderful conversationalist and they used to talk about anything and everything. As his disease progressed, though, he lost the ability to keep up in conversation.

“He stopped interacting with people. We couldn’t have conversations anymore. He was quiet, and he didn’t show much emotion,” Kim says.” There were times when he would show more emotion or become upset. But for the most part, he was quiet.”

Kim found herself grieving the father he used to be.

“I had always been able to have great heart-to-heart conversations. We are both sensitive and emotional and very deep,” she says. “He was a painter and an artist. We could talk about life, the afterlife, and deep topics. I felt like he was no longer the dad that I had for all these years before.”

Some of Kim’s most treasured memories as a caregiver are the times when she would lie in bed with her parents as they fell asleep — just as they used to do for her when she was a child.

“They liked my company as they fell asleep. We would pray together,” she says. “It was a very beautiful way of role reversal. I was the one sending them softly to sleep.”

Kim came to look at caregiving as a gift.

“It was not easy, but I was happy to care for them in the same way that they once cared for me. I needed to do that because I loved them, and I loved what I had with them,” she says. “Even though the person you love is gone, you still love them. And you will always love the memories you have made.”

Why trust our experts?