Key takeaways:

David Rothman was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and found it difficult to communicate — until a baby’s presence brought him joy.

This encounter inspired his wife, Phyllis, to invite more children to visit him and to use baby doll therapy to comfort him.

Phyllis says these efforts significantly improved David’s well-being and happiness.

Five years after his Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, David Rothman was unable to communicate with the people around him. He never spoke, which is why Phyllis, his wife of 60 years, will never forget the day in 2023 when she and David met a mother and her newborn in the lobby of David’s care facility.

“We walked over, and David looked at the baby and smiled, and actually said the words, ‘That’s a baby,’” Phyllis says, describing how David’s face lit up at the encounter.

It was a revelation, says Phyllis, 84, of Berkeley, California, a retired social worker who was dedicated to her husband’s care.

Rediscovering the joy of babies

There was something about that infant’s presence that made David happy. Here, finally, was a way Phyllis could make him smile.

As a caregiver, “it is a terrible feeling to be so helpless and powerless in the face of this disease, she says. “But I can make life better for him.”

Finding live babies who could visit him, and giving David a realistic doll, allowed her to do that.

Bringing comfort through doll therapy

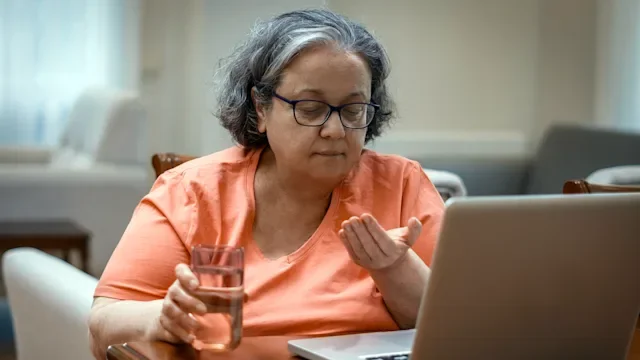

Phyllis learned about baby doll therapy. It involves giving a person with dementia a lifelike doll or realistic stuffed animal to provide comfort and a positive focus. It can also ease depression and reduce agitation.

Phyllis brought David a weighted doll: a girl with curly light brown hair and a pink onesie. Its eyes and mouth didn’t open.

“David now has his doll,” Phyllis wrote, as she journaled her husband’s progress. “He is engaged and stimulated by the doll. He smiles and kisses the doll. Other residents are entranced by the doll as well. Occasionally, the doll is kidnapped and has to be rescued.”

Caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s can be overwhelming. Read one woman’s tips and how she learned to accept help.

Caregiving can stretch on for years. Here’s how one family learned to be flexible in the face of Alzheimer’s.

How do you keep a loved one mentally engaged when they have dementia? Here are one daughter’s tips.

Spreading joy through intergenerational visits

Finding real children to visit David was more of a challenge, Phyllis says. But after seeing how babies made her husband beam, she tried to recruit families for visits.

She called, emailed, and texted day care centers and Mommy and Me-type groups. At a block party, she met a couple with a 1-year-old. She told them about David and asked if they’d be willing to visit him. They were.

“We talked to coordinate the timing of the visit, taking nap schedules of both into account,” Phyllis says.

During a walk with a friend, Phyllis saw a man taking his baby out of the car. She approached, told him about David, and asked if he’d visit him.

“Before I could get the words out, he emphatically said, ‘Yes,’ explaining that he looked for opportunities to bring people joy,” Phyllis says. “The parents of these two babies had no experience with Alzheimer's. I have been so touched and warmed by their responsiveness.”

They’d schedule monthly visits lasting about 30 minutes to an hour.

“David lights up with smiles,” Phyllis wrote. “Even with his significant decline, he responds with joy. We end when either David or the baby is fatigued.”

A legacy of love

Until his death in June 2024, David enjoyed the intergenerational visits and kept “his baby” close. Phyllis now has the doll at home as she tries to spread the word about the positives of intergenerational visits and baby doll therapy.

“I’m on a mission to get the word out,” she says, adding that even taking people with dementia to a park to watch children play can be helpful.

For David, “this was a wonderful gift,” she says.

Why trust our experts?