Key takeaways:

A Foley catheter is used to drain urine in situations where you can’t urinate on your own.

Catheters are helpful if you have urinary retention, during surgeries and hospitalizations, or if you are bedbound.

Risks of having a Foley catheter inserted include infection, trauma, and discomfort.

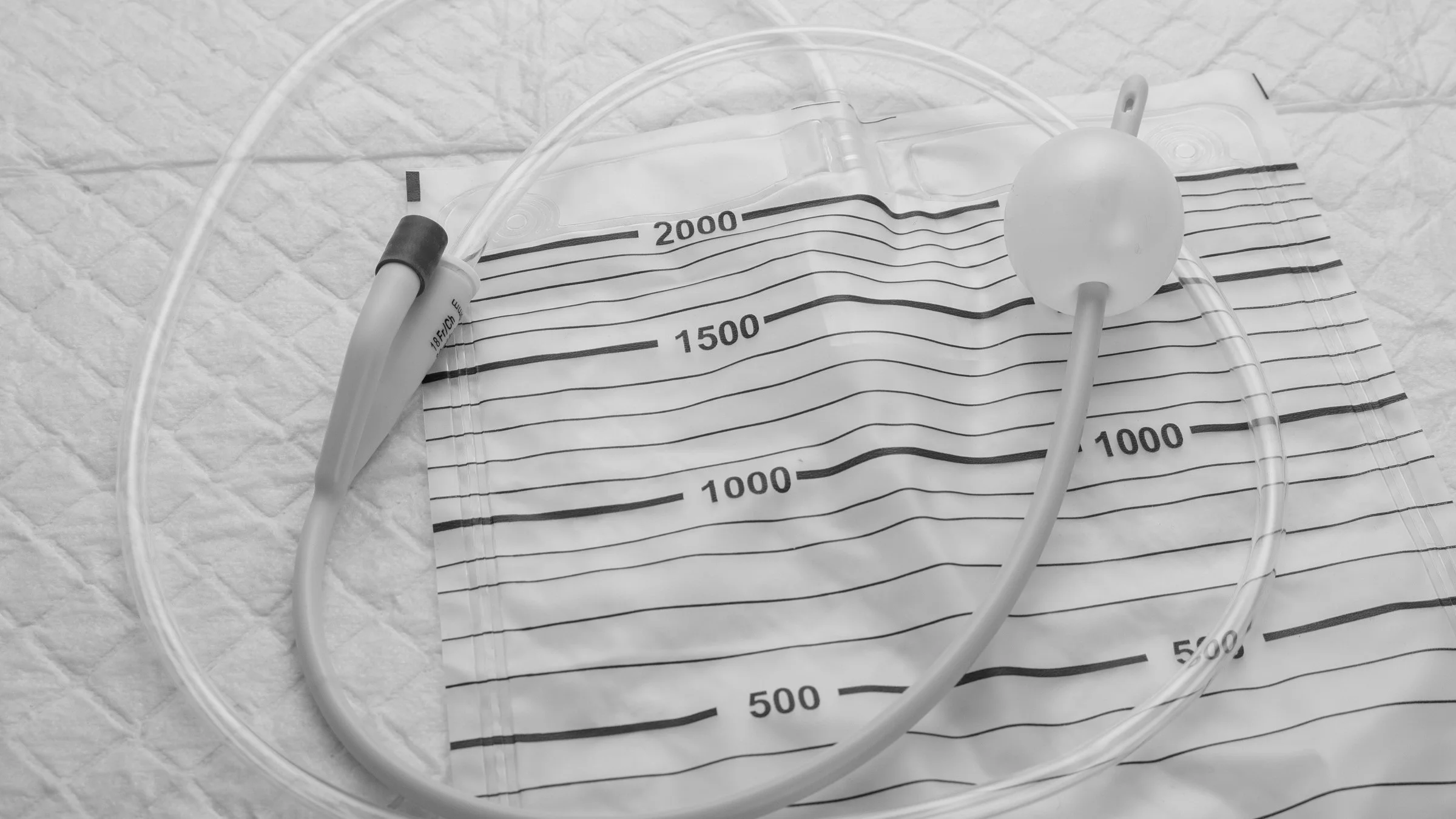

FeaturedImage

Most people don’t have to think too hard about urinating. After all, it’s something people need to do every day. But there are situations where someone can’t urinate on their own, which can be quite uncomfortable. And it can lead to serious problems for the bladder and kidneys.

Fortunately, there are tools healthcare providers can use to make sure the bladder empties when the body can’t on its own. A Foley catheter is one of these tools.

What is a Foley catheter, and what is it used for?

People have used urinary catheters for centuries. They are tubes that help drain urine from the bladder quickly. The Foley catheter is a special type of catheter that researchers invented in the 1930s. It was the first of its kind because it was designed to be “indwelling.” This means that it can stay in place to continuously drain urine over time.

Search and compare options

The design of the Foley catheter is unique because it has a small balloon at its end that sits in the bladder and holds it in place. Foley catheters come in different sizes and can be used in men, women, and children.

When do healthcare teams use Foley catheters?

Healthcare teams often use a Foley catheter to drain the bladder when someone has urinary retention or something prevents the bladder from emptying. These cases can be sudden (acute), or it can be a long-term (chronic) issue.

There are many conditions or circumstances that can lead to urinary retention. These can include:

Bladder or prostate cancer

Urethral strictures

Infections (like urinary tract infections or sexually transmitted infections)

Pelvic trauma

Spinal cord injury

Neurological disorders (like multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease)

Medications (like antihistamines, anticholinergics, and muscle relaxants)

Childbirth

There are other situations where a provider may need to place a Foley catheter, including:

Surgery with a long recovery time

Urology surgery

Strict monitoring of how much urine someone is making

Severe pelvic wounds

Immobility for a long period of time

End-of-life care

How does a provider insert a Foley catheter?

Foley catheter insertion is usually quick, but it may be uncomfortable. After cleansing the area, your provider will typically use some numbing gel and lubricant so you’re comfortable.

Read more like this

Explore these related articles, suggested for readers like you.

Then they’ll insert the catheter through the urethra into the bladder. Once urine starts draining, it confirms the catheter is in the right place. To keep the catheter from sliding out, there’s a very small balloon at the end of the Foley they inflate with water. This balloon tip of the catheter rests inside the bladder.

Finally, they’ll secure the catheter tubing to your thigh with a strap to keep it safely out of the way. The urine will drain through the tubing into an attached bag.

How do you care for a Foley catheter?

Proper Foley catheter care is key in preventing infections and other complications. This includes cleaning your catheter and managing the catheter bag. If you need to care for a Foley at home, your provider will give you specific instructions on how to do it in a safe and clean way. We’ll overview the main steps here.

Cleaning a Foley catheter

When preparing to clean or handle your catheter, you should always wash your hands with soap and water.

It’s important to clean your genital area, upper thighs, and buttocks with soap and water at least once a day. Avoid cleaning with strong solutions like antiseptics. They can irritate any sensitive skin areas.

You should also clean the catheter tubing twice a day. You can do so by wiping it with a soapy, wet washcloth and patting it dry.

Managing catheter bags

The first step in managing your catheter bag is regularly inspecting it. Make sure there are no kinks in the tubing that can prevent urine from flowing. And keep the collection bag below the level of the bladder. This is so urine doesn’t flow from the bag back into the bladder.

You should regularly empty urine collection bags, before they get too full. A “leg bag” is small enough that you can strap it to your leg during the day. It doesn’t get in the way of clothing or walking, but you’ll need to empty it regularly. You can use a larger “night bag” overnight that hooks onto the side of your bed. It’s larger, so you don’t need to empty it overnight.

If you’re using the catheter long term, experts recommend to avoid routinely changing the catheter. That’s because it increases the risk for infection. But you may have to change your catheter if you develop complications, like a blockage, damage to the tubing, or an infection.

What are the potential risks of a Foley catheter?

While Foley catheters are useful in allowing the bladder to empty, there are potential complications. Your risk of complications increases the longer you have the Foley catheter in place. These complications may be due to infectious or noninfectious causes.

Infectious complications

One possible complication of having a Foley catheter is a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI). This happens when germs from your skin and rectal area travel up the catheter into the bladder. It can lead to infections of the bladder, kidneys, and even the bloodstream.

CAUTI is the most common type of hospital-associated infection. There are 1 million cases in the U.S. each year. Older adults, people with diabetes, and people with long-term Foley catheters are at highest risk.

Symptoms of a CAUTI include:

Fever and chills

Bladder pressure or pain

Confusion

Weakness

The best ways to prevent a CAUTI are to properly care for your Foley catheter and limit how long it’s inserted. At some point, almost everyone with a long-term Foley catheter will have bacteria in their urine. It may not lead to any signs or symptoms of an infection and usually doesn’t need treatment. If a CAUTI develops, the catheter should be removed or exchanged. And your provider will figure out the best antibiotic treatment.

Noninfectious complications

There are other possible risks of Foley catheters that aren’t related to infection. These noninfectious complications can include:

Urine leaks around the catheter

Blockage of the catheter

Strictures of the urethra (narrowing of the tube where urine flows out of the body)

Pain at the site of the catheter

Hematuria (blood in the urine)

Accidental removal of the catheter

Perforation of the urethra (the catheter goes through the wall of the urethra)

Increased risk of bladder cancer

Some people experience ongoing problems even after the Foley catheter is removed. These include bladder spasms, leakage, and a sense of urgency to urinate. And some people can have difficulty starting and stopping urination.

Is a Foley catheter painful?

Unfortunately, many people with a Foley catheter find it uncomfortable. Up to 55% of hospitalized adults with a Foley catheter experience pain. In some cases, inserting and removing the catheter can be painful. Other reasons a Foley catheter may be painful include:

Allergy to the catheter material

Catheter size (too large)

Crusting inside the catheter or around the tip of the penis

Accidental pulling, tension, or traction on the catheter

Irritation to the bladder wall

Catheter blockage leading to bladder fullness

Can a person have sex with a Foley catheter in place?

Yes, it’s possible to have sex while a Foley catheter is in place. You can loosely tape the catheter out of the way of the vagina. And you can loop the catheter near the penis or loosely tape it to accommodate an erection. Then you can place a condom over the penis and catheter.

Sex with a Foley catheter may be physically uncomfortable. And people can have concerns about their self-image. It’s important to ask your provider about any questions you might have on how the catheter will affect intimacy.

Are there alternatives to a Foley catheter?

There are some alternatives to placing a Foley catheter. Depending on your specific needs, options may include:

Suprapubic catheter: goes through a small hole in your lower belly

Intermittent straight catheter: a single-use catheter you use a few times per day

Timed voids: scheduled urination

External condom catheter: fits over the penis like a condom to collect urine

There are risks and benefits for each treatment. If you or your loved one are wondering about a Foley catheter, make sure to ask your provider about all of your possible options.

The bottom line

Foley catheters can be an important tool for passing urine when you can’t do so on your own. But they need a lot of care to decrease the risk of infection. If you aren’t sure if you need a Foley catheter, it’s a good idea to consider the alternatives. Be sure to ask your provider about the risks and benefits as you discuss your treatment plan.

Why trust our experts?

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI).

Chapple, A., et al. (2014). How users of indwelling urinary catheters talk about sex and sexuality: A qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice.

Cravens, D. D., et al. (2000). Urinary catheter management. American Family Physician.

Feneley, R. C. L., et al. (2015). Urinary catheters: History, current status, adverse events and research agenda. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology.

Hollingsworth, J. M., et al. (2013). Determining the noninfectious complications of indwelling urethral catheters. Annals of Internal Medicine.

Jacobsen, S. M., et al. (2008). Complicated catheter-associated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews.

MedlinePlus. (2021). Indwelling catheter care.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (2019). Symptoms and causes of urinary retention.

Newman, D. K. (2006). Urinary incontinence, catheters, and urinary tract infections: An overview of CMS Tag F 315. Ostomy Wound Management.

Saint, S., et al. (2018). A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. Journal of the American Medical Association.

Serlin, D. C., et al. (2018). Urinary retention in adults: Evaluation and initial management. American Family Physician.

Shepherd, A. J., et al. (2017). Washout policies in long-term indwelling urinary catheterisation in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Werneburg, G. T. (2022). Catheter-associated urinary tract infections: Current challenges and future prospects. Research and Reports in Urology.

Wilson, M. (2008). Causes and management of indwelling urinary catheter-related pain. British Journal of Nursing.