Key takeaways:

Location turns out to be a major factor in which statin a patient is prescribed.

People are searching for various statins at similar rates at which they’re actually prescribed in U.S. regions.

Prescribing patterns, patient interest, and pharmaceutical marketing may explain regional variation in statin use.

Statins are one of the most commonly prescribed medications in the U.S. for high cholesterol. But according to new research from GoodRx, the many different statins vary in popularity across the country. Where you’re located is associated with which statin you’re googling and prescribed.

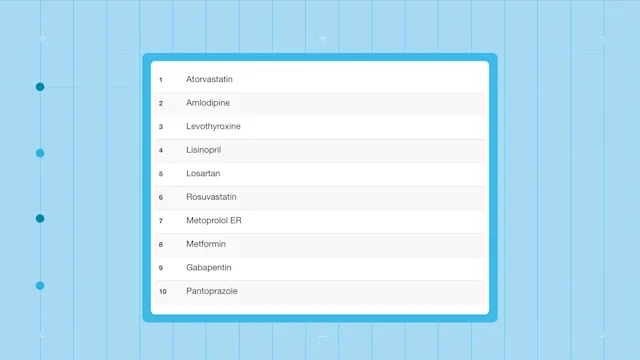

Atorvastatin (Lipitor) accounts for a little over half of statin prescriptions in the U.S. each year. But while atorvastatin is the most popular statin, there are a number of other statins, including pravastatin (Pravachol), simvastatin (Zocor), rosuvastatin (Crestor), and lovastatin (Mevacor). They all treat high cholesterol but differ in active ingredients, interactions, strength, side effects, and cost.

Below, we walk through the relationship between fills and Google searches for statins and observe the regional variations at play. Our research is based on an analysis of statin prescriptions filled through the Medicare Part D prescription drug program and search data from Google Trends.

The relationship between Google searches for statins and prescription fills

Nationally, search interest for each of the top 5 prescribed statins correlates closely with fill rates. On the whole, it makes sense that consumers are googling for medications at similar rates at which these medications are prescribed. It’s likely that people are hearing about the medication through their providers and/or advertisements and searching online to learn more about them.

Plotted below is the distribution of prescription fills for the five top-prescribed statins versus the distribution of Google searches for each of those statins. Fills and searches line up pretty closely. Atorvastatin, for example, makes up 46% of all searches for statins and 53% of statin prescription fills. Pravastatin, a less popular statin, accounts for 10% of searches and 10% of statin prescriptions.

One difference is that the number of searches for rosuvastatin (26% of total searches) outpaced the number of prescription fills (14% of total fills).

Why the mismatch? We found that people are actually searching far more for Crestor, or brand rosuvastatin, compared to other brand statins. Marketing and brand awareness seem to be influencing the popularity of both Crestor and its generic, rosuvastatin: The chart below shows that along with searches, fills for rosuvastatin and Crestor are generally on the rise.

Generic rosuvastatin, whose cash price is nearly half the cost of Crestor, entered the market in 2016 – 13 years after Crestor. But given the high ad spend on Crestor, it makes sense that consumers are learning about and then searching for the brand as opposed to the generic.

Unfortunately, disproportionately higher brand awareness does have downstream effects: Even though generics exist for all statins, 1 in 5 patients still use brand statins. That can increase the overall out-of-pocket medication costs for consumers.

Read more like this

Explore these related articles, suggested for readers like you.

Rosuvastatin and Crestor aside, the search trends generally match up with the fill trends at the national level. Now, let’s dive deeper into how your location can determine which statin you’re searching for and prescribed.

Where each statin is most popular

As we mentioned above, atorvastatin is the most popular statin across the country. But there are still places in the country where atorvastatin is relatively more or less popular.

Below, we mapped the popularity of the top 5 statins in different parts of the country. Teal states mean the statin is relatively less popular in that area. Brown states mean the medication is filled at higher rates than the national average for that statin. For example, atorvastatin is highly prescribed in the Pacific, making up 60% of all statin fills there — this equates to an extra 7 patients per 100 filling atorvastatin as compared to the national average.

On the other hand, pravastatin and rosuvastatin have the highest fills in the South, while simvastatin is relatively more popular in the West North Central states.

This trend resembles a report we published 2 years ago. However, since then, there have been some regional changes. In the next section, we walk through how some medications have increased or decreased in their respective hot spots (the browner zones of the country where the statin has relatively higher usage).

Regional statin popularity has been changing

The popularity of some statins has shifted recently. For example, atorvastatin strengthened its rank in the Pacific between 2016 and 2020. Two years ago, we reported that atorvastatin fills were already high in the Pacific in 2016 at 6.2 points above the national average (or an extra 6 patients per 100 taking the medication). Over the years, the popularity of atorvastatin increased to 7 points above the national average (or an extra 7 patients per 100) by 2020.

However, the chart below shows that between 2020 and 2022, searches for atorvastatin in the Pacific were down (though fills were still higher than the national average).

Further, pravastatin was popular in Southern states in 2016: About 4 extra patients per 100 were prescribed it there compared to the national average. This trend still holds true in 2020, but the effect cooled off as the years went by: Only 3 additional patients per 100 were prescribed pravastatin in the South in 2020 compared to the national average. Likewise, searches for it are also trending down in the South.

What accounts for the regional variation?

When medication use varies for a reason like location, it’s important to investigate if the variation may affect the quality and cost of care a population receives. Below, we outline some of the likely reasons why statin use varies across the country.

Provider bias

Many factors can result in physician prescribing pattern variations. For example, doctors may follow the prescribing patterns of other doctors in their area.

In an earlier report, we also found that prescribing can vary by specialty: Primary care providers (PCPs) prescribe simvastatin at higher rates than cardiologists, perhaps due to PCP reluctance to switch to more recently developed statins.

Pharmacological differences

Statin usage is associated with an increase in blood sugar and an increased risk of diabetes. For example, the popularity of pravastatin in the South correlates with what the CDC calls the “diabetes belt,” or the high diabetes prevalence in the South and Southeast regions of the U.S. Since pravastatin is one of the safest statins for people with diabetes, it’s reasonable that fills for it are higher in the diabetes belt.

Patient interest

Patients can also actively work with their provider to select a medication based on side effects, medical history, and more. So, perhaps patients in the Pacific are simply asking their doctor for atorvastatin more than patients elsewhere are.

What we know for sure is this: People in the Pacific are searching for atorvastatin more than patients elsewhere. And variation in search patterns matches up very closely with prescription fill regional variation.

Of course, the question becomes: Why are people around the U.S. searching for statins at different rates? Well, it holds true for almost anything — even interest in Taylor Swift varies state by state.

Summing it up

Overall, many factors can influence which statin you’re prescribed, including location, provider beliefs/biases, marketing, and evolving research on statin effectiveness.

Just because you live somewhere where a drug is less or more popular doesn’t necessarily mean you’re taking the “wrong” medication. There’s no clear answer as to which statin is the “best,” per se. But atorvastatin and rosuvastatin have been found to be the most effective at reducing LDL cholesterol.

Given the multitude of factors that operate both inside and outside of the doctor’s office, it’s important to stay informed about the high cholesterol medications available. Even though brand names may be more familiar to you and/or your provider, generics work exactly the same and are just as effective. Our statin guide and talking with your doctor are both great places to start thinking about what statin may be best for you.

Co-contributors: Jeroen van Meijgaard, PhD, Diane Li, and Tori Marsh, MPH

Methodology

CMS Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Claims: We used the Medicare Part D Prescribers - by Provider and Drug dataset. We summed prescription fills for generic atorvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, or lovastatin and all its associated brands for each year between 2016 and 2020, per state. We rolled up the state-level fills to the regional level based on state groupings in the U.S. Census Regions and Divisions and computed the fill share for each statin. Finally, for each statin, we computed regional deviation from the national average by subtracting the regional level fill share by the national level fill share.

Google Trends: We pulled state-level relative search values using the pytrends API for Google Trends for the search terms “atorvastatin,” “lipitor,” “lovastatin,” “mevacor,” “pravastatin,” “pravachol,” “rosuvastatin,” “crestor,” “simvastatin,” “zocor,” “flolipid” for each year between 2016 and 2022. Values for 2022 are based on the time period January 1, 2022 to August 15, 2022. Due to the five-term query limit within Google Trends, we ran a query to compare each term in the term list to a control term (“high cholesterol”) that was relatively more popular than all terms in the term list (but not so popular that it normalized the terms we were interested in to 0). The relative search values for each search term were summed into statin drug groups if they were brand/generic equivalents. For each year, we obtained the share of each statin drug group's relative search value to the summed total of all stain drug groups’ relative search values, by state. We averaged the share of each statin drug group’s relative search value to the region-level, weighted by the matching year of the 5-year estimates of total state population from the American Community Survey (the 2021-2022 data were weighted using 2020 5-year estimates because that is the latest data available). The regions are based on state groupings in the U.S. Census Regions and Divisions. We computed the regional deviation from the national average for each statin drug group for each year by subtracting the regional level relative search value share by the national relative search value share.

References

Fleischman, W., et al. (2016). Association between payments from manufacturers of pharmaceuticals to physicians and regional prescribing: cross sectional ecological study. BMJ.

Hajar, R. (2011). Statins: Past and present.

Harrington, R. A. (2017). Statins—Almost 30 years of use in the United States and still not quite there. JAMA.

Haymarket Media. (2007). Ad spend helps Crestor outpace Lipitor growth: Bloomberg.com.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S.). Division of Diabetes Translation. (2015). CDC identifies diabetes belt.

Sattar, N., et al. (2010). Statins and risk of incident diabetes: A collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials.

Sbarbaro, J. A. (2001). Can we influence prescribing patterns?.

Statista Research Department. (2022). Healthcare and pharmaceutical industry digital advertising spending in the United States from 2011 to 2023.

Why trust our experts?