Key takeaways:

More than 37 million Americans live in counties that lack a sleep medicine specialist. Over half of these counties are located in the South.

West Virginia, Kentucky, Alabama, Ohio, and Mississippi have the highest estimated rates of sleeplessness and the highest number of counties without a sleep medicine specialist compared to other parts of the country.

Southern U.S. counties without sleep medicine specialists and with the highest rates of sleeplessness also have higher rates of diseases associated with insomnia than the national average. These diseases include diabetes, obesity, hypertension, heart disease, depression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

One out of every three Americans doesn’t get enough sleep. But GoodRx Research finds that more than 37 million Americans live in counties without a board-certified sleep medicine specialist.

Even more concerning: Counties with poor access to sleep specialists also have higher rates of diabetes, depression, hypertension, heart disease, and obesity than the national average.

Below we highlight counties in which many residents are currently untreated for sleeplessness and those that require additional specialized care.

80% of U.S. counties with high estimated rates of sleeplessness are in the South

To identify U.S. counties with the highest rates of untreated sleeplessness (“sleepy counties”), we looked at counties with high estimated rates of insomnia and below-average fills for prescription insomnia medication. We identified nearly 400 such counties, and 4 out of every 5 were located in the South.

In these sleepy counties (the orange-colored counties below), the average percentage of the adult population getting inadequate sleep and not receiving prescription treatment is 40%. This amounts to more than 9.3 million adults.

If left untreated, these adults are at greater risk for diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, depression, heart disease, and obesity.

States with the highest number of counties with high estimated rates of insomnia and low fills for sleep medication were:

West Virginia (39 out of 55 counties, or 71% of counties)

Kentucky (85 out of 120 counties, or 71% of counties)

Alabama (24 out of 67 counties, or 36% of counties)

Ohio (30 out of 88 counties, or 34% of counties)

Mississippi (23 out of 82 counties, or 28% of counties)

This amounts to 3.2 million sleepless people. Ohio (1,290,116), Kentucky (834,635), Alabama (522,336), West Virginia (383,829), and Mississippi (232,285) also had the highest number of adults in need of sleep medicine intervention.

Midwestern and Southern states generally have a higher share of their populations living in rural areas. These areas already have limited healthcare infrastructure, and this may explain why they have lower-than-average prescription claims for insomnia medication.

In fact, our study confirms reports indicating that sleep disturbances in these regions have gone largely unaddressed since the 2010s.

Read more like this

Explore these related articles, suggested for readers like you.

Take our insomnia poll

One in five sleepless adults living in high-risk counties have no access to sleep specialists

Clearly, much of the South is in need of sleep interventions. But few of these counties have a sleep medicine specialist nearby.

While primary care providers can generally assist with sleep treatments, sleep medicine specialists often go through additional training. They can diagnose and treat sleep disorders, such as insomnia, through sleep hygiene education and prescription medication.

As seen in the map below, 269 of the 390 “sleepy” counties do not have a practicing sleep specialist. These counties are home to 5.1 million adults, with 2 million suffering from inadequate sleep.

People in these counties are also at high risk for comorbidities, such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension, heart disease, and chronic respiratory disease, which are associated with chronic untreated insomnia.

As shown above, 1 million of the sleepless adults living in counties with no sleep specialist are located in just a few states: Kentucky, Georgia, West Virginia, Virginia, Mississippi, and Alabama. Kentucky has a single sleep center for its 4.5 million residents.

So why do these counties lack a sleep specialist? It may be due to a national shortage of these professionals. What’s more, setting up a sleep medicine practice can pose financial challenges, and many of these counties have a high percentage of residents living in rural areas (86% on average). That makes it difficult for healthcare professionals to establish practices in these areas.

The health landscape for adults living in high-risk counties is worse

Unfortunately, lack of sleep is not the only thing that people in counties without a sleep specialist may suffer from. In fact, compared to the national average, those in high-risk counties live 2.5 less years on average and are more likely to struggle with chronic health conditions.

As shown above, diabetes rates are 12.7% in counties without sleep specialists compared to 10.6% of the national average. Hypertension affects 37.8% of adults in counties without sleep specialists, compared to the 32.7% national average. A similar trend exists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease, and obesity.

What’s more, counties with high sleeplessness had a lower median income than the national average. They also had higher rates of uninsured adults, higher rates of unemployment, and a higher percentage of rural residents. That means this population may have fewer resources to cover healthcare costs and live in areas with less access to healthcare.

These findings illustrate that sleep specialists are critical for lowering the risk of health conditions associated with sleep deprivation. For example, sleepy counties had higher rates of smoking. Cigarettes contain nicotine, a stimulant that has been shown to worsen insomnia and may partly explain the higher rates of sleeplessness in these areas.

Sleep counties also have higher obesity rates than the national average. Research suggests loss of sleep affects hormones that result in net weight gains, as well as poor eating patterns.

Finally, sleepy counties have a higher rate of depression than the national average (insomnia and depression have been shown to be highly related conditions). And research suggests that the treatment of insomnia may lower rates of depression.

Summing it all up

So what can you do if you live in one of these counties and struggle with sleep?

The first step is to speak with your primary care provider. There are various treatment options, including improving sleep hygiene, practicing cognitive behavioral therapy, and taking prescription medication.

If you want to see a sleep specialist, see if your health insurance will cover the cost. A primary care provider can give you a referral to these specialists. You can also search for a sleep medicine specialist through the American Academy of Sleep Medicine website.

Methodology

County-level health and demographic estimates: To better understand the extent of Americans’ sleeplessness in 2023, we used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s PLACES: Local Data for Better Health database (CDC PLACES) to get county-level, age-adjusted estimates for sleeplessness, as well as the prevalence rates of diseases associated with chronic sleep deprivation: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, coronary heart disease, asthma, depression, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Sleeplessness in this dataset is defined as an adult that reported, on average, sleeping less than 7 hours in a 24-hour period. Data for Florida and Connecticut was incomplete in the 2023 dataset and was instead sourced from the 2022 CDC PLACES dataset. Health insurance coverage, primary care provider ratio, median household income, and life expectancy were sourced from the 2023 County Health Rankings Data. Rural and urban county population data was sourced from county-level urban and rural information for the 2020 Census. Household size estimates were sourced from the American Community Survey 5-Year table B25010_001E.

Sleep medicine prescribers: To identify and geolocate certified sleep medicine prescribers, we used Healthlinks Dimension data, which has the most complete source for physician and healthcare professional information. We filtered for healthcare professionals that held either an MD, DO, NP, and PA; had a sleep medicine subspecialty; and were listed as active practitioners at the time the data was pulled in February 2024. We identified more than 7,350 professionals, as displayed below.

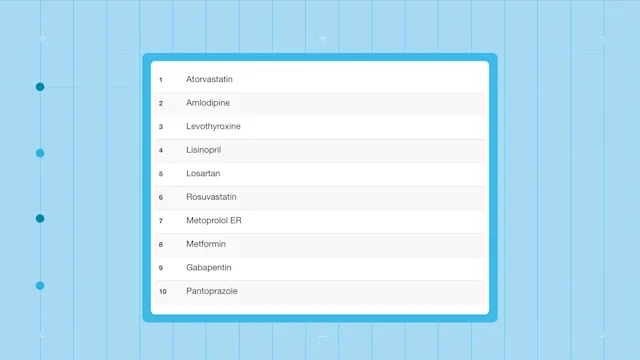

Prescription claims: We also used a nationally representative prescription dataset to identify insomnia medication claims across the country. It included the following prescription medications filled in 2023: acetaminophen pm, acetaminophen/diphenhydramine, Advil PM, Ambien, Ambien CR, Belsomra, Dayvigo, diphenhydramine, Doral, doxepin, doxylamine, Edluar, estazolam, eszopiclone, Excedrin PM, flurazepam, Halcion, Hetlioz, Hetlioz lq, ibuprofen pm, Intermezzo, Lunesta, melatonin, Motrin PM, Nyquil, Nyquil Cough, Quviviq, ramelteon, Restoril, Rozerem, Silenor, tasimelteon, temazepam, trazodone (<= 150 mg), triazolam, Tylenol PM, Unisom, zaleplon, zolpidem, zolpidem ER, Zolpimist, Zzzquil.

County classification: To identify counties that were most in need of sleep medicine intervention, we classified every county into one of four groups of sleeplessness, based on the percentile of their estimated rates of insufficient sleep reported in the CDC Places dataset. We then took the counties in the top percentile of sleeplessness and flagged counties that had fewer prescription claims for insomnia medication than the national average. This method let us identify counties at the national level that not only had high rates of sleeplessness, but also were not receiving medical treatment. Moreover, we used prescription fills as a proxy for severe medical intervention, since the first line of treatment is typically behavioral changes.

Statistical analysis: To test for group-wise differences, we performed a Welch's t-test using 0.05 as the level of significance.

References

Banks, S., et al. (2007). Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

Boland, E.M., et al. (2023). Does insomnia treatment prevent depression? Sleep.

Cafer, A., et al. (2020). Healthcare landscapes in the South: Rurality, racism, and a path forward. Center for the Study of Southern Culture, University of Mississippi.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). PLACES: Local Data for Better Health, County Data 2023.

Colten, H.R., et al. (2006). Chapter 3: Extent and health consequences of chronic sleep loss and sleep disorders. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: An unmet public health problem. National Academies Press.

Duan, D., et al. (2023). Connecting insufficient sleep and insomnia with metabolic dysfunction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

Grandner, M.A., et al. (2012). Sleep disturbance is associated with cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Journal of Sleep Research.

Nuñez, A., et al. (2021). Smoke at night and sleep worse? The associations between cigarette smoking with insomnia severity and sleep duration.Sleep Health.

Robards, K. (2023). Why sleep doctors are turning to private practice. American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

Soomi, L. et al. (2024). 10-year stability of an insomnia sleeper phenotype and its association with chronic conditions. Psychosomatic Medicine.

Staner, L. (2010). Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Medicine Reviews.

Why trust our experts?